The Argentine Grandmothers Who Resisted the Junta

Haley Cohen Gilliland’s A Flower Traveled in My Blood looks at the efforts of a human rights group to find the children and grandchildren who were disappeared by a dictatorship.

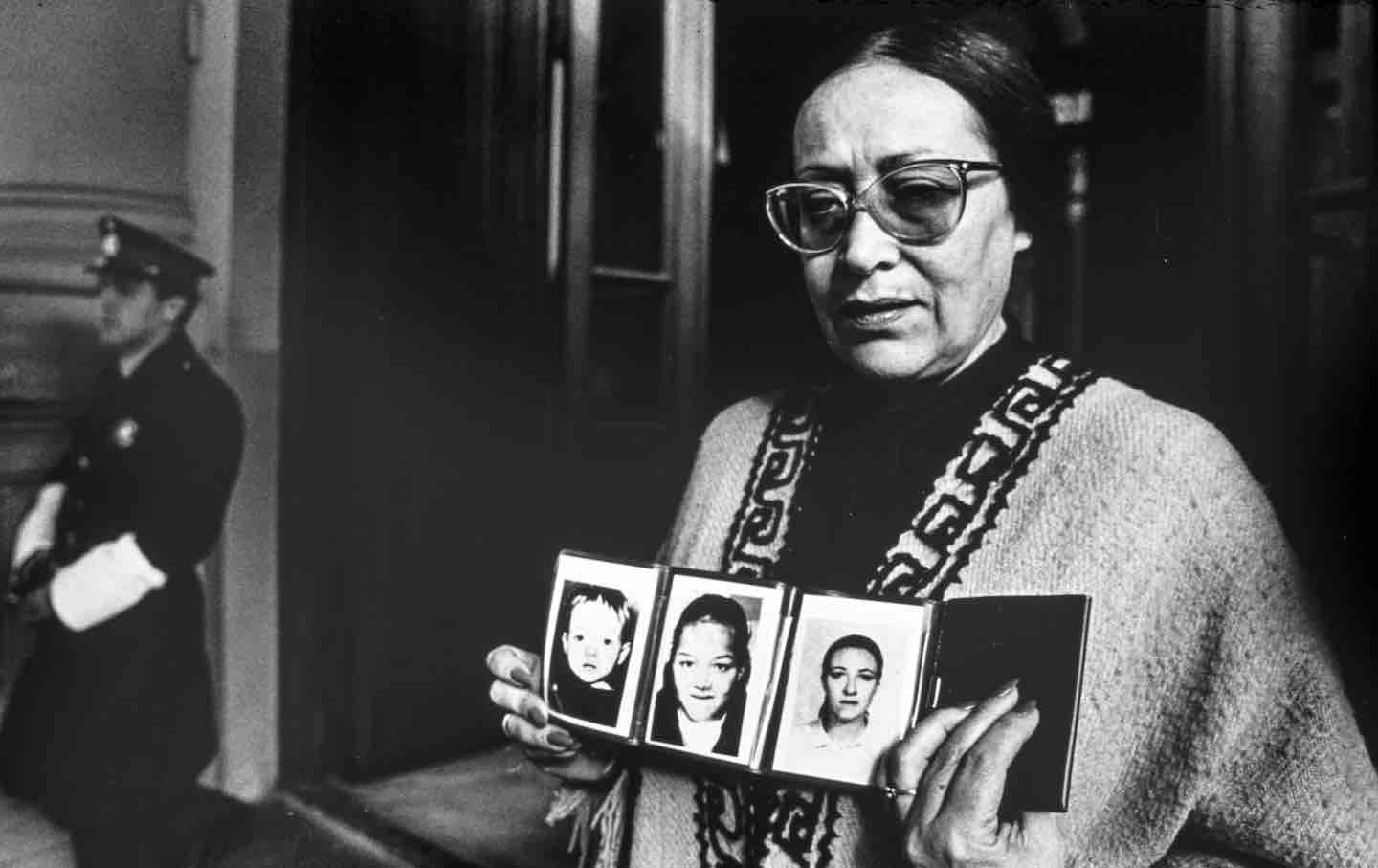

Matilde “Sacha” Artes, of the Grandmothers of Plaza de Mayo, in Buenos Aires, 1985.

(Ricardo Ceppi / Getty Images)Guillermo Pérez Roisinblit, né Rodolfo, was born in the basement of the Navy School of Mechanics, or Escuela Superior de Mecánica de la Armada (ESMA), in Buenos Aires in 1978. Today, the former naval compound is a UNESCO World Heritage Site, with a museum dedicated to the estimated 30,000 victims of the dictatorship that ruled Argentina from 1976 to 1983. At the time, however, it was one of the country’s most notorious death camps.

Books in review

A Flower Traveled in My Blood: The Incredible True Story of the Grandmothers Who Fought to Find a Stolen Generation of Children

Buy this bookRoisinblit’s mother, Patricia, was an obstetrician, and his father, José, owned and operated a toy store. Both had previously been involved with the Montoneros, a left-wing guerrilla group that opposed and sometimes violently resisted Argentina’s military junta. Both were abducted—Patricia from their Palermo home and José from his shop in the Buenos Aires suburb of Martinez. And both ultimately vanished without a trace. The couple’s daughter, Mariana, who was 15 months old when she witnessed her pregnant mother’s kidnapping, was left to live with José’s family, while the newborn Rosinblit was adopted by one of his parents’ captors, an Air Force officer named Guillermo Gómez, and spent the first 21 years of his life unaware of his true identity or the circumstances of his birth.

During that time, Patricia’s mother, Rosa, searched for him ceaselessly, first on her own and then as a member of the Grandmothers of Plaza de Mayo, an offshoot of the Mothers of Plaza de Mayo. Both groups publicly defied the junta by demanding to be told the whereabouts of their missing sons and daughters—children whom the regime had disappeared. Since the dictatorship’s fall, the Grandmothers have focused on locating the hundreds of people born in captivity and reuniting them with their families.

Roisinblit is one of the 140 stolen grandchildren recovered to date, the most recent of whom was identified earlier this month. He’s also one of the central characters in Haley Cohen Gilliland’s A Flower Traveled in My Blood, an enthralling history of a human rights movement whose mission remains as urgent as ever. Through Roisinblit’s journey of self-discovery, as well as the travails of the Grandmothers who aided him and countless others, Gilliland interrogates what it means to pursue—and ultimately find—justice for the victims of these crimes against humanity.

The Mothers and Grandmothers of Plaza de Mayo were both forged in tragedy by historical forces that extended well beyond their country’s borders. In 1976, after two years of chaotic rule rife with inflation and political violence, a group of military officers led by Gen. Jorge Rafael Videla seized control of the Argentine government from Juan Perón’s second wife and successor, Isabel. Together, the officers implemented what came to be known as the Proceso de Reorganización Nacional, or National Reorganization Process—a plan whose generic name belied a lethal project to dismantle trade unions and neutralize the left more broadly.

Years of state-sponsored terrorism followed, with the police and military pursuing many of the same tactics as the infamous paramilitary group, the Argentine Anticommunist Alliance, or Triple A, that had operated during Isabel’s government. Together, they routinely tortured and disappeared political opponents real and imagined—first to clandestine detention centers like ESMA, and later aboard “death flights” over the Rio de la Plata or the Atlantic Ocean. But the dictatorship’s crimes extended well beyond extrajudicial killings: Police and military officers also frequently claimed their victims’ babies as the spoils of war.

Ironically, although the junta had outlawed political protest, it ignored at first the handful of middle-aged women who had begun marching in Plaza de Mayo, opposite the presidential palace, in April 1977. With each passing week, however, the ranks of the women grew, and after writing and sending several letters to Videla that went unanswered, they came to call themselves the Mothers of Plaza de Mayo.

That November, the Mothers captured the state’s attention, if not the world’s. Donning white handkerchiefs on their heads, they pushed their way past Argentine and US security to interrupt a wreath-laying ceremony being held in Plaza San Martin as part of a diplomatic visit by President Jimmy Carter’s secretary of state, Cyrus Vance. Several of the Mothers handed him dossiers on the disappeared; Vance accepted them reluctantly.

As the crowd dispersed, a faction of Mothers led by María Isabel Chorobik de Mariani (“Chicha”) and Alicia Zubanabar de la Cuadra (“Licha”) gathered at one end of the plaza. They shared a singular agony: Not only were their children and their children’s partners missing, but several of them had been pregnant at the time of their abduction. Together, these women formed their own group, Las Abuelas Argentinas con Nietitos Desaparecidos (the Argentine Grandmothers With Disappeared Little Grandchildren), which eventually became the Grandmothers of Plaza de Mayo.

Unbeknownst to both organizations, Argentina was just one outpost of Operation Condor, which the Latin American historian Greg Grandin has described as “an international death squad consortium.” From 1975 to 1978, US-backed intelligence operatives in Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Paraguay, and Uruguay (and later Brazil, Ecuador, and Peru) hunted political dissidents and refugees living abroad as part of a ruthless campaign to extinguish not just communism but any semblance of social democracy in South America. To achieve these ends, right-wing dictatorships engaged in cross-border kidnappings and mass executions, among other atrocities. In Argentina, these included appropriating the newborn children of those the state had captured and killed in secret.

AFlower Traveled in My Blood explores the wreckage left in the wake of this brutality. The book’s title is taken from the poem “Epitaph” by Juan Gelman, an Argentine exile whose son, Marcelo, and daughter-in-law, Maria Claudia, were fed into the “great hungry maw” of the dictatorship’s murder machine for their involvement in leftist politics. María Claudia was seven months pregnant when she was taken, and her mother, María Eugenia Casinelli, became a founding member of the Grandmothers of Plaza de Mayo. In 2000, Gelman found their granddaughter, Macarena, in Montevideo, Uruguay. She’d been given to a Uruguayan police officer and his wife at birth—one of the thousands of victims of Operation Condor.

Gelman’s poem was written years before the junta came to power, but it formed part of a collection, La Junta Luz, that he dedicated to Casinelli’s fellow activists. Here, Gilliland uses the opening line as a greater metaphor for the grief that binds these mothers and grandmothers to their missing progeny: “A bird lived in me. A flower traveled in my blood.”

At different points, A Flower Traveled in My Blood reads like a Cold War thriller, replete with betrayals, intrigue, and elaborate schemes. In one of the book’s more memorable sections, Gilliland details how several of the Grandmothers successfully smuggled their notes concerning an archive of missing persons into Argentina from São Paulo, Brazil, using a box of Brazilian truffles. “Who was going to suspect anything of the little old ladies carrying chocolates?” one would later quip.

Then there’s the story of “Gustavo Niño,” an unassuming young man who presented himself to the Mothers and Grandmothers as the grieving brother of one of the disappeared. In truth, Niño was Alfredo Astiz, a naval officer in one of ESMA’s most brutal task forces, the Grupo de Tareas 3.3, who had infiltrated the organizations as part of an intelligence operation. As the author reveals, Astiz’s polite farewell to founding Mother Azucena Villaflor following one of the group’s gatherings proved to be a “kiss of death”: Villaflor was never heard from again, and her body was subsequently discovered in a mass grave near the coastal town of Santa Teresita with fellow members Esther Careaga and María Ponce de Bianco.

If Gilliland’s primary focus is on the dictatorship and the families it destroyed, her book also functions as a biography of sorts for one of the most consequential scientists of the 20th century. By 1982, Argentina’s military rule was on its last legs, but the Grandmothers were still unable to claim the abducted children they’d been tracking without a foolproof way to establish their identities. To solve this conundrum, they turned to a geneticist named Mary-Claire King. Over the next decade, King developed a test that matched relatives more than one generation apart through their mitochondrial DNA—a breakthrough that allowed researchers to bypass the parents who had been disappeared. The author observes that this same genetic sequence would be used to identify the bodies that the Salvadoran Army buried in mass graves at El Mozote.

King’s story is one of several deftly braided into A Flower Traveled in My Blood, and yet the book belongs to the Roisinblits. In 2000, the young man now named Guillermo Gómez (after his supposed father) was working in a retail outlet in the Buenos Aires suburb of San Miguel when he was approached by a strange woman. After an awkward introduction, she sat down to write him a letter. “I am Mariana Pérez,” it read. “My parents are desaparecidos. I’m looking for my brother who was born in captivity. Someone called the headquarters of the Abuelas of Plaza de Mayo suggesting you might be him…. If you have doubts about your identity and want to come, I’ll wait for you.”

Guillermo was unnerved. He knew about the horrors of the dictatorship; its child kidnappings had even been dramatized in the Academy Award–winning film La Historia Oficial (The Official Story) 15 years before. But he refused to believe that such a story could be his own.

Still, there were things about Guillermo’s upbringing that he struggled to explain. Why did his father, a Catholic, sometimes call him “Jew” during his bouts of rage? And why did his mother once ask him how he might respond if a woman were to knock on their door claiming he was her child? Eventually, his curiosity got the better of him, and he took a DNA test at the Grandmothers’ headquarters in Buenos Aires. The sample, which was sent to King’s laboratory, indicated a perfect match with Rosa Roisinblit.

Guillermo reckoned with the results and their consequences for several years, only accepting the Roisinblits as his family after a visit to the former ESMA prison with his biological grandmother in 2005. “There, in the exact spot where Patricia had brought him into the world surrounded by torturous strangers, he took Rosa’s hand and squeezed tightly, tears streaming down their faces,” Gilliland writes.

The scene is cathartic, even exultant. But A Flower Traveled in My Blood reminds its readers that these wounds are not so easily healed. Though Guillermo came to embrace Rosa’s affections and adopt his parents’ surnames, he and Mariana grew estranged following a bitter legal fight over the government bonds issued to her as reparations for their parents’ murder. During the trial of Guillermo’s surrogate father and two others for the disappearances of Patricia and José, his sister testified plainly: “You are not looking at a happy family.”

The questions Gilliland raises have no easy answers. “To whom does identity belong?” she asks. “Is it the sole property of an individual—or does their family and their society also have a right to truth? If someone’s identity is falsified—as in the case of the Abuelas’ grandchildren—can society force truth on somebody who doesn’t want to know it?”

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →A Flower Traveled in My Blood avoids drawing any conclusions, but its unsparing portrait of the Roisinblits lays bare the limits of truth and reconciliation. Gilliland notes that after a judge ruled against Mariana in her dispute with Guillermo, the two stopped speaking altogether, “seemingly for good.”

Ifirst heard about Guillermo Pérez Roisinblit while reporting on the latest cuts to the ESMA Museum and Memory Site for the Buenos Aires Herald. Since assuming power in December 2023, President Javier Milei has enacted a series of punishing austerity measures as part of a “chain saw” plan to raze the Argentine state. These cuts have affected all areas of Argentine life, but they’ve hit the museum especially hard. In recent months, the government has laid off a number of its workers, requisitioned one of the neighboring buildings in the ex-ESMA compound, and, most recently, fired its executive director.

In May, on the 10th anniversary of the museum’s opening, Roisinblit—now a lawyer and a Grandmothers of Plaza de Mayo board member—spoke out against this government aggression: “Behind every attempt to cut the state in human rights areas is the well-known strategy of hiding what took place here in order to guarantee impunity, and this museum proves we as a society have chosen not to forget.”

That Milei has targeted such an institution is hardly a coincidence. Both he and his vice president, Victoria Villarruel, have repeatedly denied the extent of the dictatorship’s crimes, claiming that its true toll was just 8,753 people, a figure even lower than the one cited in the government’s own 1984 report, Nunca Más. (A declassified Condor intelligence memo estimated that 22,000 people had been disappeared by 1978, and most human rights organizations put the final number at 30,000.) They have likewise sought to unwind Argentina’s consensus memory policy as part of an ever-expanding cultural war that has included regular attacks on the political opposition, human rights advocates, and the administration’s critics in the press.

As Gilliland’s book makes clear, the Grandmothers of Plaza de Mayo have faced these reactionary forces before, both during the dictatorship and in the decades of democracy since. The Milei administration nevertheless poses a new threat to Argentine civil society. If history is written by the victors, then it can just as easily be rewritten, especially when it’s a history as contested and incomplete as that of a recent dictatorship.

Take a stand against Trump and support The Nation!

In this moment of crisis, we need a unified, progressive opposition to Donald Trump.

We’re starting to see one take shape in the streets and at ballot boxes across the country: from New York City mayoral candidate Zohran Mamdani’s campaign focused on affordability, to communities protecting their neighbors from ICE, to the senators opposing arms shipments to Israel.

The Democratic Party has an urgent choice to make: Will it embrace a politics that is principled and popular, or will it continue to insist on losing elections with the out-of-touch elites and consultants that got us here?

At The Nation, we know which side we’re on. Every day, we make the case for a more democratic and equal world by championing progressive leaders, lifting up movements fighting for justice, and exposing the oligarchs and corporations profiting at the expense of us all. Our independent journalism informs and empowers progressives across the country and helps bring this politics to new readers ready to join the fight.

We need your help to continue this work. Will you donate to support The Nation’s independent journalism? Every contribution goes to our award-winning reporting, analysis, and commentary.

Thank you for helping us take on Trump and build the just society we know is possible.

Sincerely,

Bhaskar Sunkara

President, The Nation