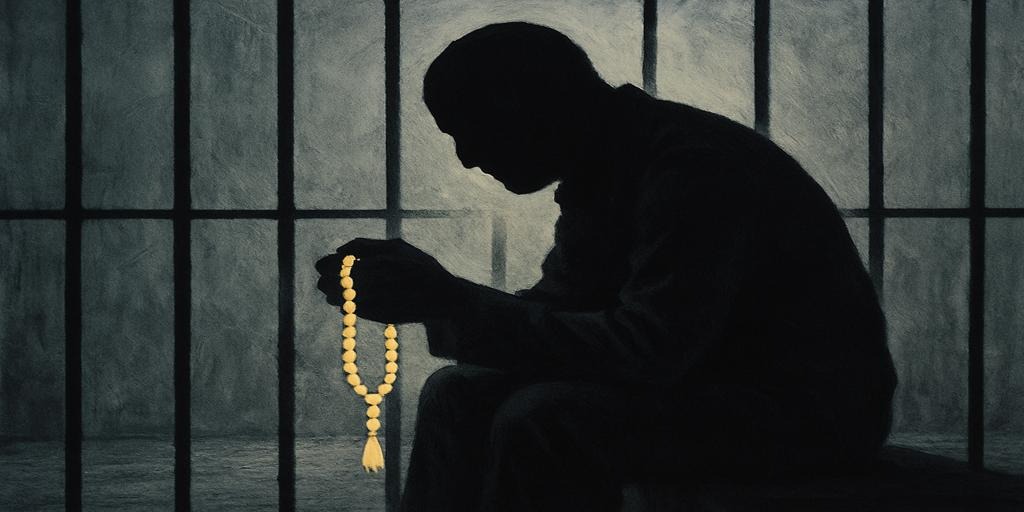

Two Muslim prisoners of conscience in Uzbekistan — both previously jailed for nonviolent religious activity — have had their sentences extended in recent months under charges that human rights observers describe as vague and politically motivated. While the cases have drawn criticism from international monitors, they also highlight the Uzbek government’s enduring fears over political Islam, concerns shaped by geography, history, and national security calculations.

Tulkun Astanov, a 54-year-old activist originally imprisoned in 2020 for defending the rights of fellow Muslims, was sentenced to an additional three years and two months in a strict-regime labor camp this May. Authorities accused him of refusing to attend morning exercises in prison and of disobeying lawful orders. Astanov, who has suffered multiple strokes in custody, submitted a written request to be excused from physical activity on medical grounds — documentation which was reportedly dismissed by prison officials. His family and legal counsel contend the new case was fabricated to prevent his scheduled release later this year. The U.S. State Department has documented repeated concerns about his treatment in its 2022 International Religious Freedom Report.

A second prisoner, Fariduddin Abduvokhidov, 30, was arrested in 2020 after participating in private Islamic study circles. He was originally given an 11-year sentence, but earlier this year, his term was extended twice: by ten years in March and an additional year in April. According to his family, the new charges relate to alleged “religious propaganda” while in detention. They say he was not fully informed of the basis of the charges and declined to appeal, citing emotional fatigue and lack of faith in the process.

International monitors, including Human Rights Watch, have raised alarm about Uzbekistan’s use of vague extremism provisions to prosecute peaceful religious expression. Trials are often held behind closed doors, with little transparency or legal recourse for defendants. In both cases, court documents have not been made available to families or the public.

Uzbekistan shares a 144-kilometer border with Afghanistan, where groups like the Taliban and ISIS-K remain active. During the 1990s and early 2000s, Uzbekistan suffered violent attacks from the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU), a jihadist group aligned with the Taliban and later al-Qaeda. Those experiences left a lasting impact on both policymakers and public opinion, contributing to an enduring suspicion of independent Islamic activism.

Several OECD democracies, including France, Belgium, and Austria, have enacted bans on face coverings in public. While controversial, those policies were introduced through public debate and are subject to judicial review. In Uzbekistan, by contrast, the lack of independent courts, competitive elections, and free media means that state regulation of religion is rarely subject to institutional checks.

Uzbekistan has made real progress in other aspects of governance. Since independence in 1991, the country has implemented reforms in public administration, economic policy, and digital infrastructure, and it is currently pursuing accession to the World Trade Organization. Engagement with the OECD and OSCE has also deepened.

For many observers, Uzbekistan’s evolution will be gradual, and should be allowed to proceed on its own terms. But the continued imprisonment of individuals like Astanov and Abduvokhidov underscores the lingering tension between state security and personal freedom. The question ahead is not whether Uzbekistan should protect itself from extremism, but whether it can do so while embracing the pluralism that defines a more open society.

At the same time, lasting democratic development will require not only rights and representation but also the consistent application of law and order. For Uzbekistan, the task is to build a system where security and justice reinforce — not undermine — each other.