Opinion: India vs Japan: Growth in numbers, gaps in development

GDP can open doors, but it is the human development indices that reveal whether people are walking through them

By Neeraj Kumar, Dr Maya K

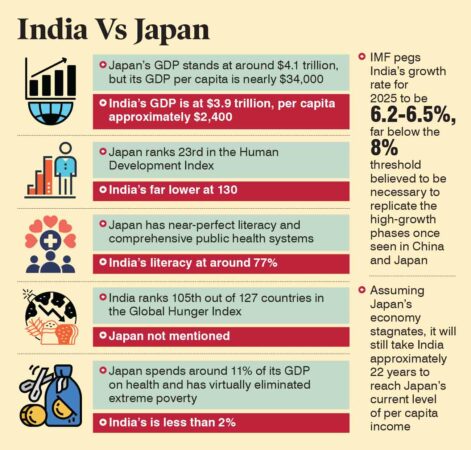

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) in its April World Economic Outlook report projected India, which is currently the fifth-largest economy, will become the world’s fourth-largest economy in 2025, with an estimated GDP of USD 4.19 trillion. This would place India just ahead of Japan, whose GDP is expected to be USD 4.186 trillion. After achieving this milestone, India will be behind only the United States, China, and Germany.

NITI Aayog Member Arvind Virmani commented that while this is still a forecast, he is confident that India will officially achieve this milestone by the end of 2025, once the full-year GDP data is available. This economic rise may inspire policymakers, economists, and citizens’ confidence. Yet, as with all proud narratives, it demands a deeper, more critical examination. Can a country truly be called “developed” or even “genuinely growing” just because it has climbed the GDP ranks? The answer requires a thorough examination of the realities beyond GDP, realities defined by health, education, equity, employment, and overall human well-being.

Riddled Story

Despite the remarkable GDP figures, India’s development story remains riddled with contradictions. One of the most pressing issues is poverty. As per the Global Multidimensional Poverty Index 2024, 234 million Indians continue to live in acute poverty, the highest absolute number in the world. Food insecurity is also a chronic problem, with India ranked 111th out of 125 countries in the Global Hunger Index. The label of a booming economy loses meaning when millions still go to bed hungry.

Healthcare remains another weak link in India’s development chain. Public expenditure on health is less than 2 per cent of the GDP, resulting in overburdened hospitals, a shortage of medical staff, and high out-of-pocket expenses for patients. The healthcare infrastructure remains alarmingly inadequate for a population of over 1.4 billion.

At the same time, access to quality education remains uneven across rural and urban areas, as well as along gender lines and socio-economic classes. The literacy rate, at around 77 per cent, lags behind many nations with far smaller GDPs.

Inequality, both economic and social, has also intensified. India ranks 108th in the Global Gender Inequality Index and 126th in the World Happiness Index. The concentration of wealth continues to rise, with a significant portion of national resources and opportunities confined to a small elite.

The labour market reflects this skewed growth. Despite an increase in GDP, employment generation remains weak. Youth unemployment stands at around 23 per cent, and a significant portion of the workforce remains engaged in informal, low-productivity jobs, particularly in agriculture and small-scale industries. This phenomenon, often referred to as “jobless growth,” highlights that rising output is not being matched by increasing incomes or quality employment.

GDP only one of the Dimensions

In contrast, Japan, despite being overtaken in GDP, offers a more balanced and mature development profile. Japan’s GDP stands at around $4.1 trillion, but its GDP per capita is nearly USD 34,000, compared to India’s approximately USD 2,400 in 2025. Japan ranks 23rd in the Human Development Index, compared to India’s far lower rank of 130, and has near-perfect literacy and comprehensive public health systems. While India struggles to meet basic health and education needs, Japan spends around 11 per cent of its GDP on health and has virtually eliminated extreme poverty.

India is projected to become the world’s fourth-largest economy, surpassing Japan, yet vast gaps in health, education, equity, and employment persist. GDP growth alone doesn’t ensure development, and India must address its human development challenges to achieve inclusive prosperity

Japan’s model is a contrasting example with important lessons: a slower-growing but inclusive and equitable economy that prioritises the well-being of its citizens. The comparison reinforces the idea that economic size does not automatically mean development. Development is multidimensional, and the GDP is only one of those dimensions. Although there are many differences between India and Japan, this comparison can help clarify the layman’s misunderstanding that growth means development.

The IMF has projected India’s growth rate for 2025 to be 6.2-6.5 per cent, which is substantial but still below the 8 per cent threshold that economists believe is necessary to replicate the high-growth phases once seen in China and Japan. Moreover, India’s capital formation rate, an indicator of investment activity, is only 24 per cent, while the ideal threshold for sustained development is around 32 per cent.

Without strong capital formation, growth may stagnate and become unsustainable in the long run.

Experts have pointed out another significant fact: India’s per capita GDP today is comparable to Japan’s in the 1950s. Assuming Japan’s economy stagnates, it would still take India approximately 22 years to reach Japan’s current level of per capita income. Furthermore, India currently falls behind countries such as Kenya, Morocco, Libya, Mauritius and South Africa in per capita GDP, underlining how far the average Indian is from benefiting equally from national economic growth.

Notable Achievements

While challenges exist, one must also acknowledge the country’s notable achievements. One of India’s key strengths lies in its domestic consumption, which accounts for nearly 70 per cent of its GDP. This reflects the growing aspirations and spending capacity of a rising middle class that plays a crucial role in stabilising and expanding the economy.

India has also made commendable mark in global trade. According to World Trade Organization (WTO) data, India ranked 7th in global merchandise imports and 14th in leading merchandise exports in 2024. The country is also witnessing a boom in digital infrastructure, fintech, and e-commerce sectors, which have the potential to generate employment opportunities and boost productivity.

Additionally, India continues to lead the world in remittance inflows, receiving over $100 billion for the third consecutive year, as per the World Bank. These remittances — accounting for over 14 per cent of global flows, serve as a financial push for millions of Indian households, contributing to rural consumption and investment.

Broader Truth

Yet, these positives cannot distract from the broader truth: India’s development remains uneven and incomplete. Rising GDP figures are necessary but not sufficient. A truly “growing” economy must also grow in inclusiveness, equity, and human well-being. It must reduce poverty, bridge inequality, empower women, and provide quality education and healthcare for all. A growing economy must ensure job-rich growth and guarantee dignity and opportunity for every citizen.

As India aspires to move to the fourth-largest economy spot, it must also aspire to become a nation where prosperity is measured not just by numbers but by the lives those numbers touch. GDP can open doors, but it is the human development indices that reveal whether people are walking through them.

(Neeraj Kumar and Dr Maya K are Assistant Professors, Department of Economics, CHRIST University, Bengaluru)

Related News

-

TCA panels lodge criminal complaints against HCA in districts

16 mins ago -

Army jawan on leave goes missing, family in distress

40 mins ago -

Star Hospitals launches Heart Failure Clinic to address rising cardiac health crisis

2 hours ago -

Four passengers, driver injured as ash tanker rams RTC bus in Khammam

2 hours ago -

Telangana Jagruthi stages protest, urges State Women Commission action over MLC Naveen’s remarks

2 hours ago -

Telangana to push Centre for justice in Krishna-Godavari water sharing, pending project clearances

3 hours ago -

Zaheerabad murder: Trio kills youth over black magic suspicion

3 hours ago -

Harish Rao holds Congress govt responsible for alarming crisis in Gurukuls

3 hours ago